How we make real meat

In 2013, our founders Mark and Peter introduced the world’s first cultivated beef burger. Their motivation for this never-before-seen process to make real meat was to address the enormous global challenges of food sustainability and food security. Starting with beef was an obvious choice, considering its production footprint.

Mark and Peter acknowledged that the world’s demand for meat was projected to keep growing. Since the beginning of their work together five years prior, they determined that the best way to make a positive global impact would be to offer people the exact same culinary experience as conventional meat. To swap meat with meat by innovating the process, rather than the behaviour.

Instead of using plant protein and fat, which needs processing and flavouring to mimic meat, they would harness the natural biological process that produces the exact same animal protein and animal fat that people enjoy every day.

In 2016, they founded Mosa Meat, and we have grown into a team of over 100 scientists, engineers and researchers. We have invested heavily in understanding the full natural process of meat. With what we’ve learned over the years, we can now let this full growth process take place, without needing to change anything in the cells, and without needing any animal components in the process (more on that later). We say “full process” because we know that all the goodness of eating beef (taste, smell, nutritional value) emerges when the cells are allowed to reach their fully matured state—becoming muscle fibers and fat tissue.

Today, we are excited to give you a peek behind the curtain and share the progress we have made towards producing real meat.

Fat Parity

Fat gives beef much of its flavor, and is responsible for the tenderness and mouthfeel of a deliciously-grilled burger—which is why we have been committed to cultivating fat and adding it to our meat.

We recently measured the “fingerprint” of our fat, as represented by its triglycerides profile (also known as lipids, these are the main constituents of animal fats). The below image shows the similarity between Mosa Meat’s cultured fat profile and conventional beef fat, as well as a comparison with coconut oil, which is commonly used in plant based products.

Left to right: Triglycerides profile of coconut oil (often used in plant-based meat fat), conventional fat, and Mosa Meat cultured fat.

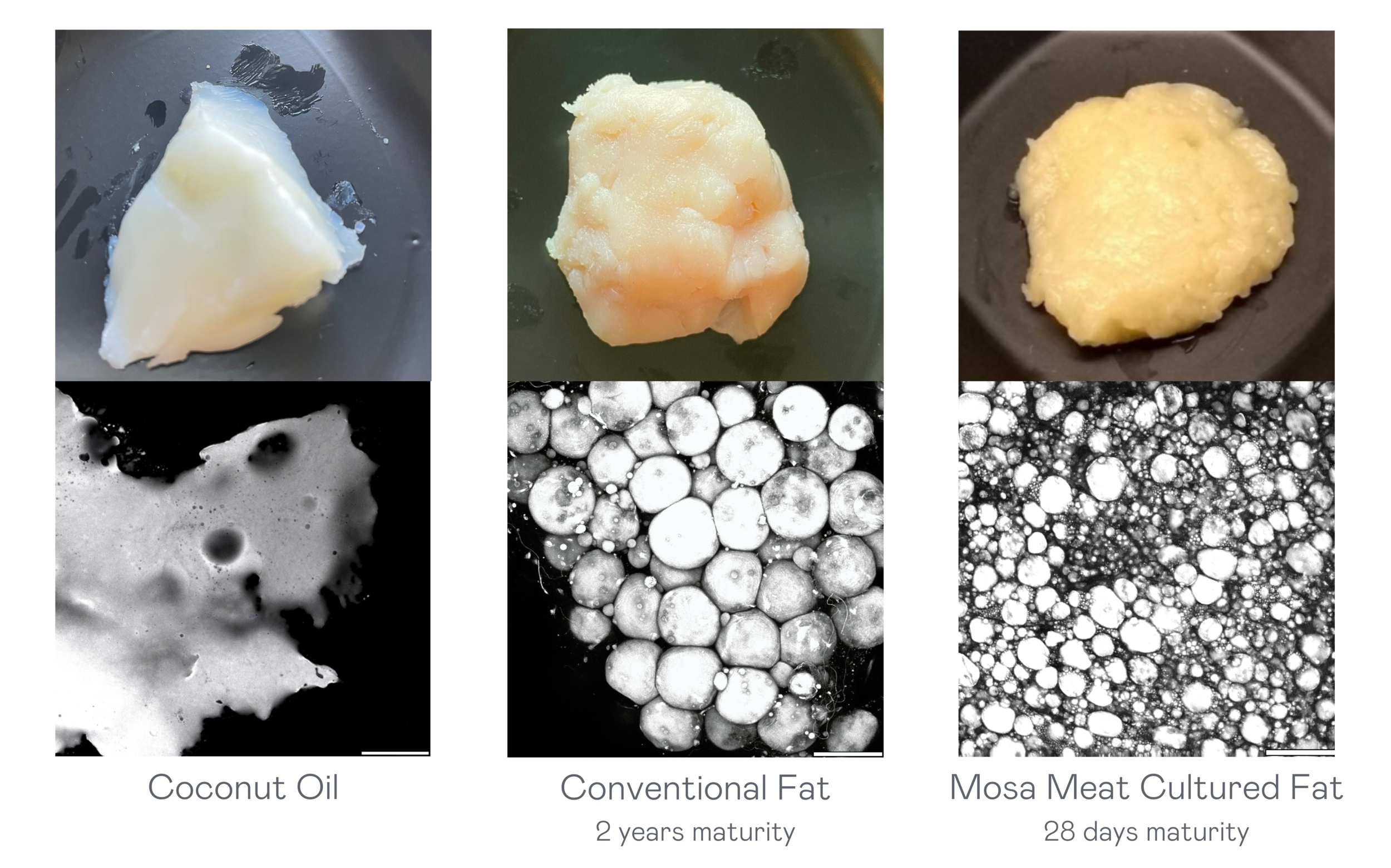

This parity is also visible through the physical resemblance of Mosa Meat cultured fat to conventional animal fat. The photographs below show that while coconut fat, conventional fat and Mosa cultured fat can look fairly similar on a surface level, there are clear similarities between cultivated and conventional fat and differences with plant based fat when we take a closer look at microscopic imagery.

Left to right: Coconut oil, conventional fat, and Mosa Meat cultured fat. Conventional fat maturation: >2 years. Mosa fat maturation: 28 days. (Scale bar: 100μm)

We can also observe parity in the composition of saturated and unsaturated fats in our cultured fat with conventional fat, versus coconut oil (below).

The levels of saturated fat in our fat are comparable and slightly lower than in conventional beef fat. We’re comparing here again with coconut oil, which is very high in saturated fat, a major albeit not exclusive component used in plant-based products. The similarity of Mosa Meat Cultured Fat with conventional fat results in a similar taste, as indeed experienced in recent tastings. As said, our goal is first and foremost to give people the exact same culinary experience as conventional beef.

Muscle Parity

Muscle fibers give meat its structure and chew, and within muscle fibers the rich colour of meat and proteins are produced. Of the more than 100 million different proteins known to science, we of course care most for meat-specific proteins, with names like myosin and actin. They look and behave very different to plant protein, and they are the building blocks of what makes meat meat.

Protein structure predictions of plant protein (left) and meat protein (right). Source: Jumper, J et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature (2021).

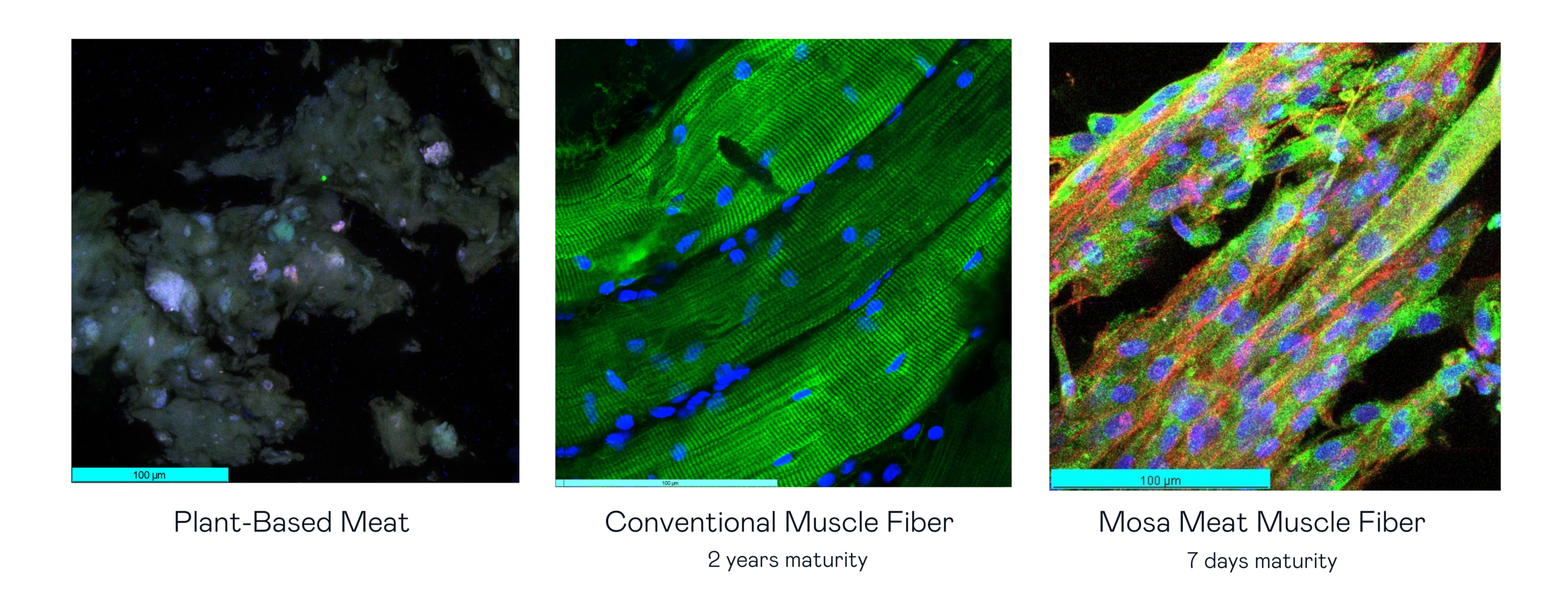

Production of these meat-specific proteins occurs as muscle fibers mature. The microscopic images below show the similarity in Mosa Meat muscle fiber structures with conventional muscle fiber, as compared to a plant-based burger.

The colours in the below images of conventional and our muscle fiber demonstrate expression of meat-specific proteins like actin, a primary muscle protein (red), desmin, an early differentiation protein (pink), and myosin (green). The blue colours represent the nuclei of cells. The plant-based image shows no actin or myosin, no cells, or any structure that resembles muscle.

Left to right: Plant-based burger, conventional muscle fiber, Mosa Meat muscle fibers. Conventional muscle fiber maturation: >2 years. Mosa muscle fiber maturation: 7 days. (Scale bar: 100μm)

Achieving the same nutritional profile as conventional meat is critical to making real beef, and we will share more about our progress in this area in a future blog post.

Optimizing Our Process For These Results

In addition to making delicious, high quality meat, we are committed to making meat that is kind to animals. We successfully removed all animal components from our process, starting with removing FBS a couple of years ago. Our animal-free process also brings down costs and increases scalability. This brings us one step closer to our goal of offering the exact same culinary experience to consumers as conventional meat, without harming any animals.

We are also proud to say the above results have been accomplished without any gene-editing. We are simply enabling the natural processes to take place. Finally, our meat is cultivated in a sterile environment, minimizing the risk of contamination, and will be antibiotic-free.

While the transformation of the global meat system will happen over years and decades to come, we remain committed to our mission to replace meat with real meat, bringing us closer to achieve Mark and Peter’s original goal.

We are very excited to share these results with you today, because we don’t just want to demonstrate our dedication to serving people the highest quality beef, but we also value openness and transparency across our emerging field of cellular agriculture.

We hope you will continue to follow us along on our journey. You can stay updated on our progress via the links below.

Crave change? Sign up to our newsletter for Mosa Meat updates and stories straight to your inbox: mosameat.com/newsletter